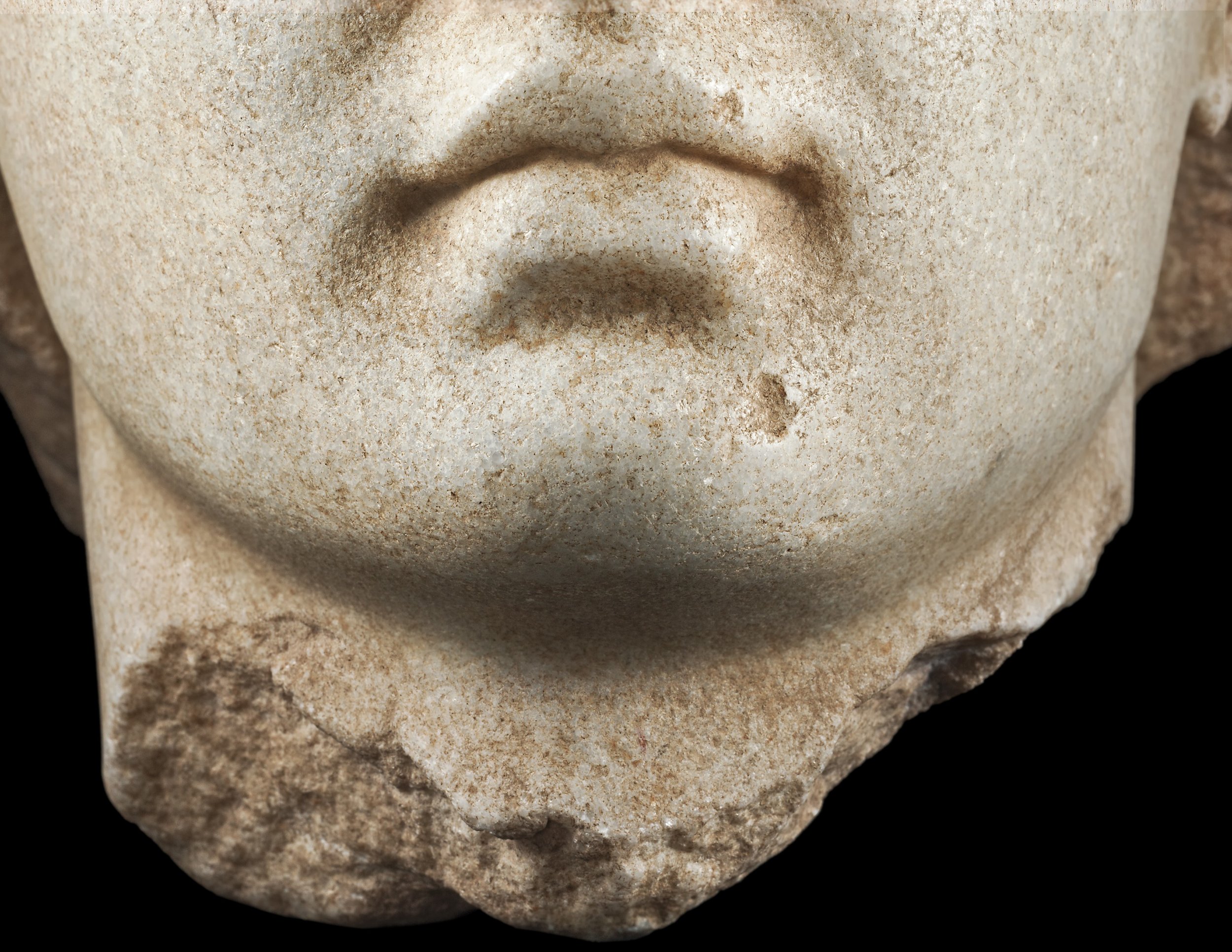

Greek, Early Hellenistic, ca. 270‐220 B.C.

Marble, probably from the Greek island of Paros

H: 31 cm

Portrait of Herakles-Alexander the Great

The International Fine Art & Antique Dealers Show

Park Avenue Armory, New York, 2013

Herakles - Alexander

Greek, Hellenistic, ca. 270‐220 B.C.

Marble

H: 31 cm

This exceptional marble head of a young man wearing the lion-head helmet presents several and fascinating research issues related to the iconography of Alexander the Great and the practices in the Greek Hellenistic sculpture. One should consider and answer a variety of questions: whether the head represents the young Herakles or the young Alexander as Herakles or Alexander simply wearing the lion-head helmet; if the portrait of Alexander: was it was created within Alexander’s own lifetime or later; how did the entire statue, to which the head belongs, look like; if the figure was single or made part of the sculptural group, etc.

The possibilities of the attribution this piece to the time of Alexander are limited by historic evidence both epigraphic and archaeological. There was a number of the representations of youthful Alexander executed during his life. When Alexander was very young, only 16 years old, he was portrayed by Leochares who made the chryselephantine statues of the members of the Macedonian ruling family that was commissioned by the father of Alexander, Phillip II, and installed in the Phillipeion at Olympia (Pausanias, Description of Greece, 5. 20. 9-10). Some years later, when he became the ruler, Alexander employed Lysippos to create statues of him. Lysippos was told to be the only sculptor allowed to cast Alexander’s image in bronze as only Apelles did it in painting and Pyrgoteles engraved it on gems (Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, 7, 125). None of these images was a representation of Alexander as god or hero; and there is no direct evidence that the cult of Alexander was already established during his reign, perhaps with the exception of some Greek cities mostly in Asia where he was granted divine honors. Ephesus commissioned Apelles a fresco painting representing Alexander with thunderbolt, i.e. in the guise of Zeus. He was greeted as the son of Zeus Ammon at the oracle of Siwa in 331 B.C. “If Alexander wishes to be god, let him be a god”- was the answer of Spartans when Alexander requested divine honors in the Greek cities reported in later tradition (Aelian, v.h. 2. 19).

The images of beardless Herakles wearing the scalp of the slain Nemean lion on coins were issued by Alexander at his lifetime, it is assumed by most scholars that this is the image of the hero and not the ruler – Alexander continued the tradition of showing on coin his legendary ancestor and patron of the royal dynasty, tradition established by his predecessors. However, other scholars admit that there are features resembling Alexander’s portraits in these representations, and they assume that the die-cutters, unwillingly or following the demands of royal propaganda, expressed the idea of divinization. As A. R. Bellinger has it: “at some times and in some places, true likeness of the king and his commanding personality inspired the hands of his artisans so that men came eventually to believe that he and Heracles were one”.1 The more critical view formulates that this happened rather after his death in 323 B.C., when the Successors, the former generals of Alexander, started to use his portrait on their coinage. Ptolemy I placed his portrait on the coinage soon after 321 B.C., since this period the head of Herakles became identified with Alexander as the deified king. On the coins issued by the Paropamisos in the former Seleucid kingdom in 190-180 B.C. the representation of the head wearing the lion skin is accompanied by the inscription “of Alexander (son) of Philip”, so there is no doubt that no longer the legendary hero but the deified Alexander is represented there. As there is no one and universally accepted portrait of Alexander/Herakles on coins and all the representations differ, it is a very hard task to distinguish the idealized portrait from a more realistic one. The fact is that they were all recognized as Alexander’s portrait by the contemporaries.

As for the representations in sculpture, there is no secure image of Alexander/Herakles executed in his lifetime. The attribution of the marble head wearing the lion skin (the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) made by E. Sjöqvist, is not accepted by most scholars in the corpus of Alexander’s portraits. The so-called Alexander sarcophagus from Sidon (Archaeological Museum, Istanbul), which is a posthumous representation dated to the last years of the 4th century B.C., shows Alexander on horseback in the battle scene and wearing the lion skin on his head. This feature is related by some scholars with Alexander’s habit to be occasionally dressed up as Heracles at banquets in his last years (Athen, XII, 537e).

Some scholars find the resemblance of Herakles head in the lion skin attached at the base of the handles of the silver alabastron from the Tomb II at Vergina with the representation of Alexander the Great at the height of his career, while P. Moreno believes that this would be the image of the young Alexander in lion skin. P. Moreno advances the idea that the statue of Alexander-Herakles was that statue of Alexander, the Invincible God, mentioned by Hypereides in early 323 B.C.

PROVENANCE

Ex- Marguerite Motte collection, Motte Gallery, Paris/Geneva, 1965;

Ex- Swiss Numismate/collector, Zurich, 1960’s;

Ex- J. L. collection, Geneva, 1977;

Ex- Art market, Geneva, 1996;

Qatar Investment, 2014

Marguerite Motte/ Motte Gallery (gallery in Geneva, active from 1932-1997)

Galerie Motte was founded in Geneva at the end of the Second World War. At that time, the art market remained underdeveloped in French-speaking Switzerland and, above all, the Geneva public was poorly prepared for the new forms of pictorial expression that the gallery was going to present to them. (In her memoirs, Marguerite Motte underlines the fact that, during her studies in Geneva, the teaching of art history stopped in the 18th century) In 1949, when the Galerie Motte held its first painting exhibition, it is the sixth gallery installed in Geneva (after the two Moos galleries, the two Benador galleries and the Athénée gallery). This will therefore contribute to introducing contemporary art to the French-speaking public. Big names are on display at Galerie Motte; from the impressionists (Degas, Renoir, Manet...) and post-impressionists (Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gaugin...) to contemporary artists; cubists (Picasso...), surrealists (Max Ernst...), abstract expressionists (Rothko, De Kooning...)... Some artists already enjoy notoriety, others are still difficult to accept by the public Geneva (This is the case for the last three names mentioned). Galerie Motte also tries to introduce unknown European and American artists, but considered innovative (The best example remains Bernard Buffet, then a beginner artist), and encourages young local painters (At the beginning of the fifties, it created the prize for young Genevan painter, then the Colombe competition reserved for Protestant artists). However, Galerie Motte is not only dedicated to contemporary art; there were exhibitions on African, Asian, pre-Columbian arts... and on some European artists of the so-called modern era. These different exhibitions are accompanied by auctions of works of art. It was during a stay in Paris that she met the auctioneer of the Drouot room; Mr Aries. The latter encouraged him to diversify these activities, because at the time Bern was the only Swiss city where public sales were organized, but these were mainly devoted to the German school. Subsequently, she organized other sales, in Switzerland, but also in Monte Carlo, in Montevideo... (with the help of the bailiff Maître Cosandier and the gallery owner-art expert Jacques Dubourg) and from 1954, she gave lectures on contemporary art. The "Motte collection" also mentions several publications of art books, developed in collaboration with Jacques Damase, which were published following successful exhibitions (for example the work "Lagravure d'Ensor"). The beginnings of Galerie Motte were modest. The first texts which refer to it give the impression that the gallery owner organizes herself almost alone to accomplish all the tasks. She transports the paintings herself in (and on the roof of) her car. Friends give him a few helping hands. Due to lack of resources, it cannot afford to hire workers. Later, she hired a staff of around ten people (drivers, booksellers, secretaries, etc.), used a freight forwarder and owned several vehicles (for transporting works, to receive clients and for her personal use). It was also at this time that it opened a branch in Paris. This golden age of the gallery seems to be between the end of the sixties and the beginning of the seventies; period when the oil market is favorable and the dollar is a strong currency. However, even with success and even surrounded by employees, Marguerite Motte continues to hold the reins of the gallery that she manages from Geneva. She works there up to fifteen hours a day. Exhibitions and sales are meticulously organized several months in advance. Looking back, Marguerite Motte admits to having organized too many exhibitions in her early days (due to lack of money), and regrets not having been able to "unburden herself" by delegating responsibilities to a personnel manager. There is no doubt that the gallery owes its success and longevity to its director. It is therefore not surprising to note that after the latter's death, the gallery went bankrupt.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

On Alexander’s representations in Heracles lion-head helmet, see:

BIEBER M., Alexander the Great in Greek and Roman Art, Chicago, 1964, pp. 48-52, 61, 64.

MORENO P., L’immagine di Alessandro Magno nell’opera di Lisippo e di altri artisti contemporanei in CARLSEN J., DUE B., STEEN DUE O., POULSEN B., eds., Alexander the Great: Reality and Myth, Rome, 1993, pp. PALAGIA O., Imitation of Herakles in Ruler Portraiture: A Survey, From Alexander to Maximinus Daza in Boreas, 9, 1986, pp. 137-151.

On portraits of Alexander the Great in sculpture, see:

Alexander the Great: Treasures from an Epic Era of Hellenism, New York, 2004, 15-29.

KIILERICH B., The Public Image of Alexander the Great in CARLSEN J., DUE B., STEEN DUE O., POULSEN B., eds., Alexander the Great: Reality and Myth, Rome, 1993, pp. 85-92.

POLLITT J. J., Art in the Hellenistic Age, Cambridge, New York, New Rochelle, Melbourne, Sydney, 1986, pp. 20-31.

RIDGWAY B. S., Hellenistic Sculpture I, The Styles of ca. 331-200 B. C., Madison, Wisconsin, 1990, pp. 108-126. The Search for Alexander, New York, 1980, pp. 98-104, 118-123, 179-181, 187.

SMITH R. R. R., Hellenistic Royal Portraits, Oxford, 1988, pp.58-64.

SJÖQVIST E., Alexander – Heracles: A Preliminary Note in Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 51 (no. 284), 1953, pp. 30-33.

STEWART A., Faces of Power, Alexander’s Image and Hellenistic Politics, Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford, 1993.