A Study by Dr. Alexander v. Kruglov PhD

Former Curator at The Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

The iconography of Nike/Victoria in ancient Greek, Roman and Byzantine art covers the time span of more than one millennium and presents a wide diversity of forms. That is to say that usually Nike, her hairstyle, wings, garment etc. was represented in a unique way throughout ancient art and civilizations, and only like that, is groundless; these features are the subject of period, style, and artistic manner.

(a)

Nike/Victoria does not have her personal individual hairstyle. Like many other deities in antiquity, she shares the type of hairstyle (i.e.: in Classical period, Zeus, Asklepios, Hermes, Poseidon have the same hairstyle and beard). The particular type represented in this present work was adopted not only for the female (Aphrodite) but also for male gods (Dionysos, Apollo). The type originated in the 4th century B.C., and it remained popular through the Late Antiquity. For example, Nike/Victoria is constantly represented with the hair-knot above the forehead on the Roman Imperial marble reliefs and Byzantine ivory plaques:

-

The Trajan column

2nd century A.D.

-

The ivory dyptich of Basilius

A.D. 541

-

The Great Trajanic Frieze

2nd century A.D.

-

Arcus Novus

A. D. 293

-

Arch of Constantine

A.D. 312-315

The two “kiss curls” in the hairstyle of Nike appear in the early Hellenistic period attested by the Aphrodite head of 330-300 B.C. (The Bartlett Head, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) and decorative works such as the gold earrings:

-

Gold earrings with pendant Nikai, The Getty Museum

225-175 B.C.

-

The Bartlett Head, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

330 - 300 B.C.

This hairstyle in question is designed of long strands; it consists of the hair parted in middle, with one part rolled on the sides, and another part bound in a knot above; the rest is combed to the back and caught up in a bun. All these features are represented absolutely correctly in this present statuette. The size and the arrangement of the loops of the knot were subject of fashion and period style - note the hair-knot of Apollo Belvedere in the Vatican, 1st century B.C., and a similar design but a very different form in the Apollo’s head in the British Museum, 2nd century A.D..

-

Apollo Belvedere, Vatican

1st century B.C.

-

Apollo’s head, British Museum

2nd century A.D.

(b) The wings and feathers are consistent with known / documented types:

(i)

Wing feathers were represented differently in ancient art depending on the time period, knowledge of bodily anatomy, artistic style, and also the material of which the artwork was executed. The type of the wings was differentiated depending on the individual iconography (an eagle or eagle-based creature and a winged Eros have different types) and composition (if the image was represented still or in motion). The representation of the feather size in this present statuette is consistent with general anatomical structure of the eagle wing and the arrangement by rows, with shorter marginal and primary covers and longer primaries and secondaries. The multidirectional disposition of the feathers is affected by the figure’s movement in the air opposing the wind. Similar representations are found in the reliefs of the Pergamon Altar, 2nd century B.C., particularly in the wings of the giant Alkyoneus to the left of Athena and Nike to her right.

-

Pergamon Altar

2nd century B.C.

(ii)

The uniform very fine carving on both sides of the wings should not be considered as something contradictory or unknown in ancient sculpture.

If a statue was designed to be placed against the wall or inside the niche, the back side would be worked roughly, or even left unfinished. When a sculpture was made with the idea to be seen from all sides, as a fully three-dimensional work, each side and part of it would be executed with detail. Such qualities would be even more precise in the works of smaller size, the statuettes, and especially in the works of great value executed from precious and semi-precious materials – which is exactly the case for the chalcedony Victory.

(iii)

The relatively small size and shape of the wings are not post-antique.

Such a type depends on the technique and material used for the execution of the artwork. For instance, smaller wings are found in the Greek terracotta figurines of the Hellenistic period.

The carver of the present chalcedony statuette was well aware of the material’s fragility; it would be extremely difficult to carve and keep intact the longer wings. On the other hand, these relatively small wings are perfectly coordinated in proportion with other projected parts of the figure. Especially, when seen in profile, the outstretched right arm, the lower folds of the chiton, and the wings form a well-balanced and harmoniously modeled structure.

-

Greek terracotta vessel with Nikai figures, The British Museum

3rd century B.C.

(iv)

Looking at Nike binding her sandal, a relief from the parapet of Athena Nike Temple on the Athenian Acropolis, 410 B.C., one should assume that the wings come from the slots cut through her double dress (she wears both the chiton and the himation), but this is not considered in a conventional representation assumed for the images of fantastic creatures.

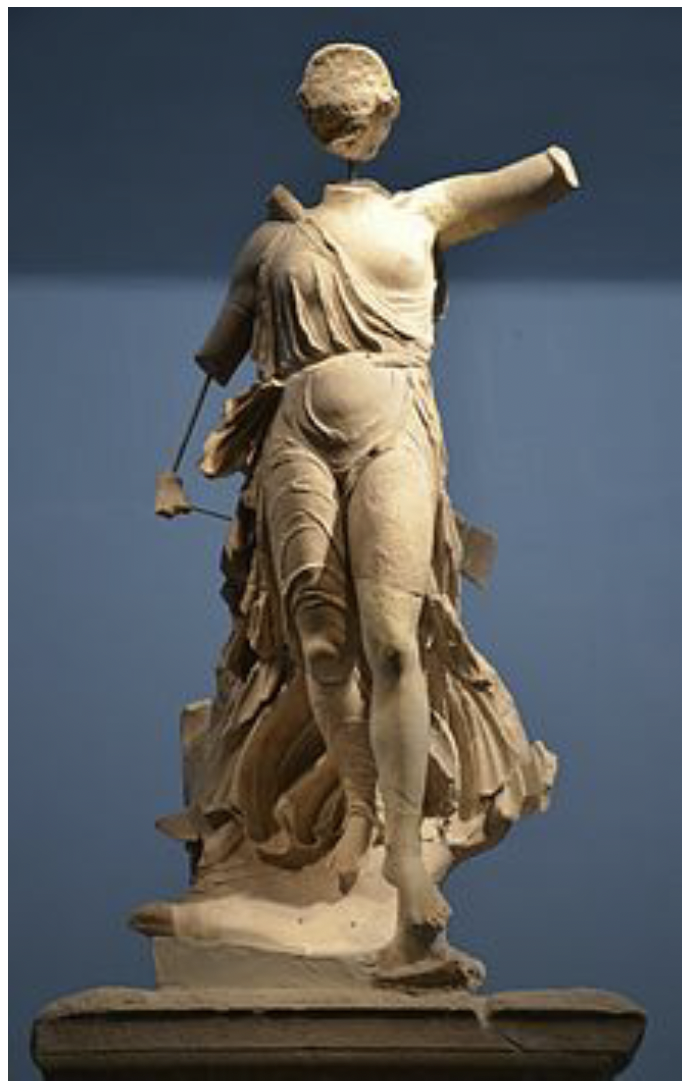

In this present statuette, the representation of the wings and the garment adopts the same conventional relationship, when the edge of the chiton is coinciding with the outer side of the wing and goes below them in the middle of the back, where, it looks, the folds of the fabric merge with the skin. The garment/wing relationship is represented similarly in the famous statue of Nike of Samothrace, 3rd – 1st century B.C., in the Louvre.

-

Athena Nike Temple, Athenian Acropolis

410 B.C.

-

Victoriola

ca. 5th century A.D.

-

Nike of Samothrace, The Louvre

3rd – 1st century B.C.

-

Nike of Samothrace, The Louvre

3rd – 1st century B.C.

(c)

No matter the size (statuettes or statues), such features were represented differently at different chronological periods. As Aphrodite can appear fully dressed, semi-dressed, or naked, the iconography of Nike incorporates her images with both breasts covered, both breasts bare, or with one breast left bare.

-

Nike by Paionios, Archaeological Museum, Olympia

Greek, 425-420 B.C.

one breast left bare; the navel is not articulated

-

Bronze statuette of Victoria, Christie’s New York, 4 June 2015

Roman, 2nd century B.C.

with both breasts bare

-

The Barberini ivory plaque, The Louvre

Byzantine, 6th century A.D.,

Victoria with one breast left bare

(d)

The goddess is represented in a descending flight with clear differentiation in the position of her limbs. She is already standing on her left foot and gently touching the surface with the toes of her right foot. The fact that she is still in a rapid motion is stressed by her spread wings, the outstretched right arm, while her left arm is pulled back. The head is slightly turned to the side. There is a great accordance in the simultaneity of these actions - that’s how the garment responds to the body movement, the voluminous folds of her long chiton are swirling around her waist and blown against and behind the legs (the billowing drapery is characteristic for the representations of moving/dancing figures in Greek art of the Late Classical – Hellenistic periods).

-

Nike, The Louvre

terracotta, 2nd century B.C.

-

Victoriola

ca. 5th century A.D.

(e)

The anatomy of the feet is articulated well enough to shape the ankles, the toes and the heels, and does not need any more detailing. Naturally, the artist pays more attention to the primary features, which would be considered the most essential for the recognizing of this specific image.

(f)

Most of the corpus of ancient figurines made of chalcedony, rock crystal, plasma, amethyst, are preserved fragmented, without the feet and, especially, without their original bases or attachments. The present statuette is exceptional in that it fully preserves the dowel under the figure’s proper LEFT foot, which is shaped for the insertion. The tapering shape is comparable to the dowels well-known among the bronze statuettes. With both feet touching the surface, this dowel is sufficiently large to hold the figurine in place (supposedly, on an orb).

-

Victoria on an orb, The State Museums, Berlin

bronze, 1st - 2nd century A.D.

-

Victoriola

ca. 5th century A.D.

(g)

In a small-scale work like this, it is natural that the arm is attached to the body directly by the index finger, rather than by an additional strut. The struts are typical and appropriate for a large marble statuary, so this is simply not applicable to the present statuette.

-

Eros of the Centocelle type, The Capitoline Museums, Rome

marble, 2nd century A.D.

The struts in a statue

(h)

The left hand appears oversized because it misses the attribute; it would appear perfectly balanced while holding an object (a palm branch, a crown).

-

Victory holding a palm branch in her left hand, The Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

sardonyx cameo, 1st century B.C.

(i)

The technique of separate carving of the body elements and their assembling in a statue by means of pins is attested for stone statuary much larger in scale, so, again, this is not applicable to the present statuette.

Moreover, most ancient statuettes of semi-precious stones which preserve their limbs demonstrate that they were carved entirely from single pieces of stone.

-

Herakles, chalcedony

Princeton University Art Museum, H: 3.5 cm

-

Asklepios, amethyst

D. J. Content collection. H: 5.7 cm

-

Herakles, rock crystal

The Walters Museum, Baltimore, H: 7.5 cm

-

Herakles, chalcedony

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, H: 6.3 cm

(j)

To enable an important attribute (a military trophy, a crown) to be clearly seen / highlighted, it would be executed separately, and possibly, from a different material (gold, silver, bronze, or color stone) and attached to the right hand.

-

Solidus of Constantine I with Victory

holding a military trophy in her right hand and a palm branch in her left, A.D. 335-336.

(k)

As explained above (part d), the composition of the statuette under examination is based on a perfectly natural attitude. The trunk-like figure would have probably been a choice for a craftsman of limited artistic skills and possibilities. Obviously, we deal here with an extraordinary and highly ambitious commission (comparable only to that of the Roman and Byzantine emperors) and an incredibly skillful artist, with the resources of an imperial workshop. Both the commissioner and the artist would have probably approved on creating such a masterpiece, a tour de force of gem carving, that no one could be able to surpass in its craftsmanship. The present safe condition of Victory is an eloquent evidence of great control of balance and integrity in the sculptured figure.

-

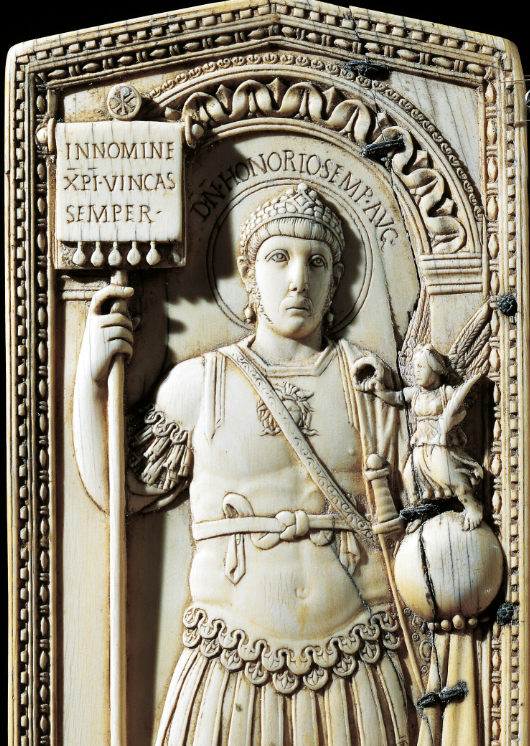

Aosta Cathedral Treasure

Emperor Honorius holding an orb with Victory, ivory, A.D. 406.